Recent studies conducted by the University of Liverpool have shed light on one of nature’s most formidable phenomena: underwater avalanches. Unlike their terrestrial counterparts, which can be visually tracked, these subaqueous catastrophes often occur beneath the waves, leaving little in the way of immediate evidence. Dr. Chris Stevenson and his research team embarked on a groundbreaking project that combined various data sources to map out a colossal underwater avalanche, unveiling its astounding growth and destructive potential.

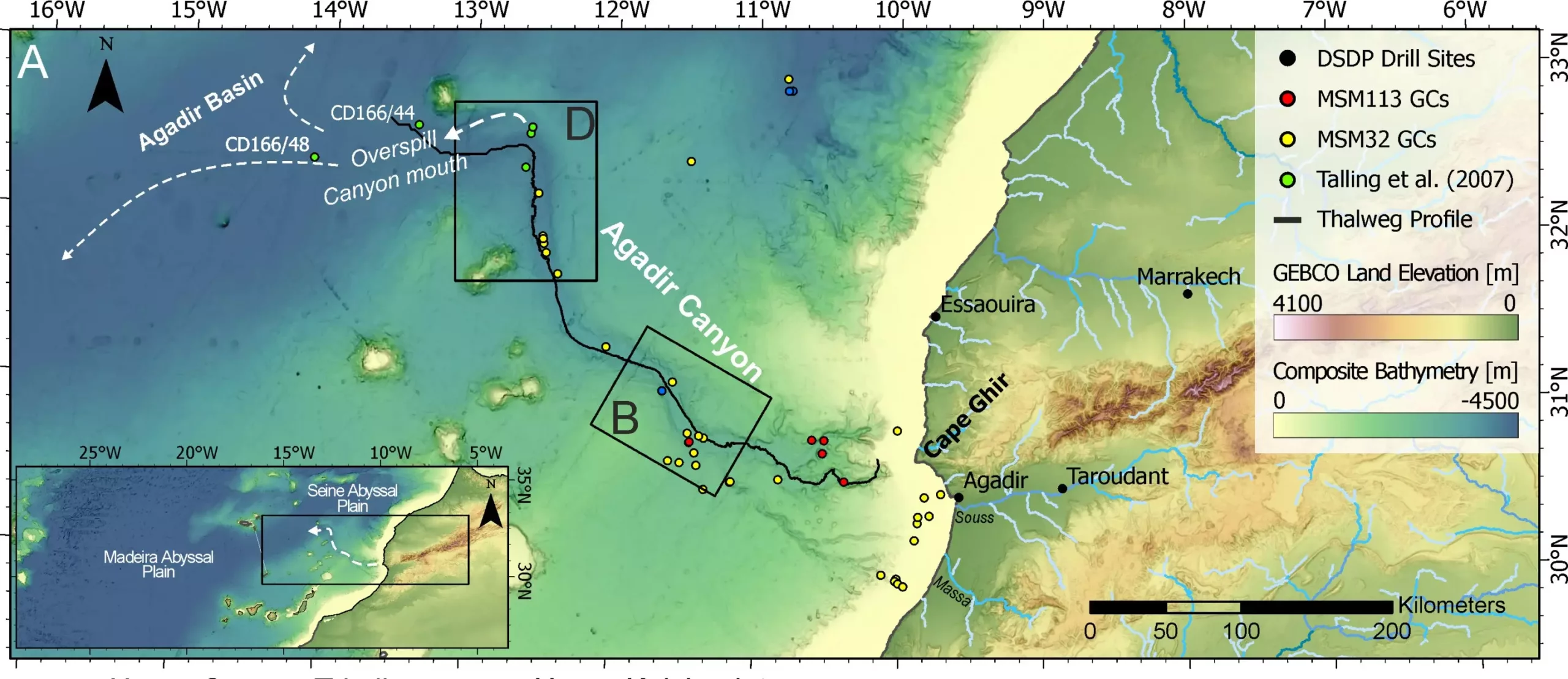

This investigation reveals how a small seafloor landslide transformed into a massive wave of sediment—over 100 times its original size— as it coursed through the Agadir Canyon, a significant submarine canyon located off the North West coast of Africa. In their study, published in the journal Science Advances, the researchers document the avalanche’s journey across 2,000 kilometers of the Atlantic Ocean seafloor, providing a detailed account of the sediment movement that can considerably reshape underwater topographies.

The Scale of Destruction

Given that underwater avalanches can carry immense amounts of material, the scale of destruction is both staggering and unsettling. Starting as a seemingly innocuous event with a volume of only around 1.5 kilometers, the avalanche ultimately carved out a 400-kilometer-long canyon and extended hundreds of meters up its walls, moving cobbles over 130 meters high. What is particularly astonishing is the sheer force of this avalanche, which traveled at nearly 15 meters per second—equivalent to the speed of a car on a bustling highway.

To visualize this phenomenon, one can compare it to a skyscraper rushing from Liverpool to London at speeds exceeding 40 miles per hour. In the avalanche’s wake, it dug out a trench 30 meters deep and 15 kilometers wide, burying an area larger than the United Kingdom under a meter of sediment. Such comparisons emphasize not just the scale of this underwater event, but also the transformative impact it has on the ocean floor.

The research team’s revelations point to a distinct mechanism governing the extreme growth of underwater avalanches. Dr. Stevenson notes that this avalanche expanded to a growth factor of at least 100, a stark contrast to the modest growth observed in snow avalanches or landslides, which typically only reach four to eight times their original size. This discovery raises intriguing questions about the fundamental characteristics of underwater avalanches and the factors that allow them to amplify so dramatically.

Dr. Christoph Bottner, a Marie-Curie research fellow involved in the study, expressed interest in the peculiarity of these underwater events. The phenomenon of an avalanche growing to such unprecedented proportions invites further exploration into the dynamics of sediment transport in marine environments. The extreme growth patterns seen in this study could be indicators of broader trends in similar underwater locales, potentially transforming how scientists approach the study of these natural events.

The implications of this research extend beyond scientific curiosity; they present significant concerns regarding geohazards that may jeopardize underwater infrastructure, such as the internet cables that underpin global communication. The study, led by a coalition of research institutions, particularly highlights how these submarine fluctuations can pose risks to cables that form the foundational pathways of the internet—essential for contemporary societies.

Professor Sebastian Krastel, a key contributor and head of Marine Geophysics at Kiel University, underscores the importance of reassessing the geohazard risk evaluations associated with underwater avalanches. The study’s findings compel marine geoscientists to consider the potential hazards stemming from what were previously thought to be minor slope failures. This paradigm shift in understanding could help in developing strategies to mitigate risks to essential subsea infrastructure, ensuring the longevity and stability of these critical communication channels.

The collective work engaging with sediment samples and data analyses over several decades illustrates the commitment to unraveling the complexities of the seafloor dynamics. As further investigations are proposed, the potential for discovering additional underwater avalanche events presents an exciting frontier in marine geology.

By enhancing our understanding of underwater avalanches—what triggers them, how they propagate, and their ecological ramifications—researchers may pave the way for improved predictive models. This greater foresight could transform not only scientific knowledge but also practical applications, such as better safeguarding technology vital to contemporary life against the capricious forces of nature lurking beneath the waves.

The revelations made by the University of Liverpool not only enrich our understanding of underwater avalanches but also challenge long-held assumptions in marine geology, highlighting the need for ongoing exploration and research in our ever-evolving relationship with the planet’s oceans.

Leave a Reply