Anorexia nervosa is an intricate mental health disorder that poses significant challenges to the individuals afflicted by it. Characterized by self-imposed starvation, an overwhelming fear of gaining weight, and severe distortions in body image, this illness transcends mere eating habits. It is a psychological condition deeply intertwined with physiological factors that complicate its understanding and treatment. Recent research is shedding light on the neurobiological underpinnings of anorexia, suggesting that alterations in neurotransmitter functions within the brain could play a crucial role in its manifestation and maintenance.

Anorexia nervosa does not occur in isolation; it is a disorder that has robust associations with several neurochemical activities, particularly those involving neurotransmitters. A groundbreaking study has indicated that the imbalance in neurotransmitters may contribute to the onset of anorexia. The researchers highlighted alterations in neurotransmitter systems, specifically mentioning the mu-opioid receptor (MOR), which appears to be elevated in patients with the disorder and is implicated in regulating not only appetite but the pleasure derived from eating.

Understanding the influence of MORs offers a vital piece of the puzzle in comprehending anorexia. In the brains of those with anorexia nervosa, the presence of higher MOR availability could explain why individuals might derive a sense of gratification from starvation rather than food. This up-regulation contrasts starkly with findings in obesity, where a down-regulated opioid system is observed. This dysregulation in neurotransmitter dynamics suggests a radical difference in how the brains of individuals with varying eating habits process rewards and maintain homeostasis.

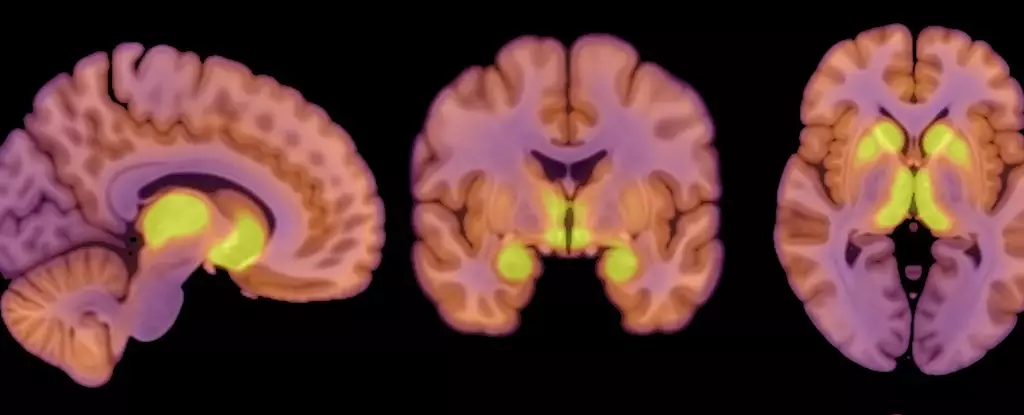

The research involved a sample of 26 women, including 13 diagnosed with anorexia nervosa and 13 healthy controls, all of whom were aged between 18 to 32. Each subject underwent positron emission tomography (PET) scans for MOR measurement and glucose uptake analysis. The design of the study focused on creating comparable cohorts with distinct body mass index (BMI) categories, allowing researchers to draw meaningful contrasts between the physiological and psychological states of individuals with anorexia and healthy subjects.

Previous studies had already indicated that the brain consumes a significant portion of a person’s total energy, approximately 20%. The researchers aimed to explore how reduced caloric consumption influenced brain energy dynamics. Astonishingly, despite the caloric deficits faced by anorexia patients, their brains were able to maintain glucose uptake similar to that of healthy individuals. This finding suggests an innate priority that the brain assigns to its functional needs, safeguarding itself even amidst severe malnutrition.

The brain’s ability to protect itself, even when the body is malnourished, speaks to the complexity of anorexia. While an anorexic state is physically debilitating, the brain attempts to sustain its activity until the body’s reserves are critically depleted. This protective mechanism may underscore some of the psychological resilience observed in patients, who often exhibit an obsession with maintaining control over food intake and weight, serving to shield them from the mental turmoil associated with their condition.

Furthermore, understanding the relationship between MORs and brain functionality during episodes of anorexia raises questions about the cause-and-effect dynamics between nutritional deficits and neurochemical changes. Are elevated MORs a driving force behind the disorder, or are they a consequence of prolonged undernutrition? Without further research, these crucial questions remain unanswered, emphasizing the need for thorough investigations into how these neurobiological alterations interact with behavioral and psychological symptoms.

Despite the significant insights provided by the study, critical limitations must be addressed. The exclusive focus on female participants illustrates a gap in understanding anorexia in broader populations, particularly in males. Additionally, while the small sample size offers initial insights, it limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should include larger, more diverse cohorts to verify the conclusions drawn from current research.

Moreover, the lack of a direct link established between MOR activity, glucose uptake, and individual eating behaviors leaves room for exploration. Investigating how changes in neurochemistry directly correlate with behavioral outcomes could yield essential insights that might redefine treatment strategies for anorexia.

Anorexia nervosa remains a multifaceted disorder that blends psychological distress with complex neurobiological changes. The recent identification of neurotransmitter dysfunctions, particularly concerning MOR availability, provides a fresh perspective on potential therapeutic targets and treatment frameworks. By continuing to unravel the intricate pathways through which the brain’s signals influence eating behaviors, the medical community may be better equipped to address this formidable disorder, ultimately improving outcomes for those who suffer from it. As research progresses, the hope is that a more comprehensive understanding will pave the way for innovative treatments that consider both the mind and brain in concert.

Leave a Reply