For centuries, scientists have passionately debated the origins of Earth’s continents, a pivotal development that set the stage for the emergence and evolution of life. The prevailing theories surrounding the formation of these land masses often hinge on geological processes that mirror those observed today. However, recent research led by David Hernández Uribe from the University of Illinois Chicago has brought a fresh perspective to this long-standing debate by challenging established beliefs and offering alternative explanations.

The Research Paradigm: Exploring Magma Formation

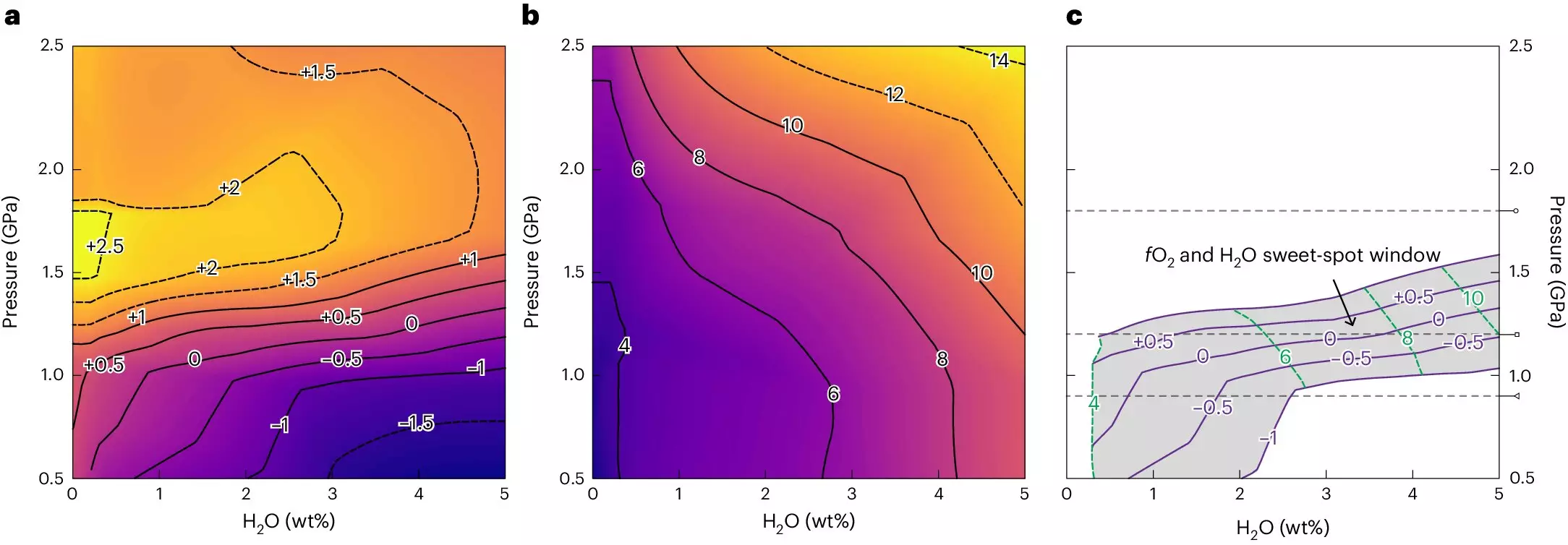

Hernández Uribe’s groundbreaking study, published in *Nature Geoscience*, employs advanced computer modeling techniques to investigate the formation of magmas. Magma, the molten rock beneath Earth’s surface, acts as a critical element in understanding the geological history of continents. The study specifically examines magmas that correspond with the unique compositional signatures found in zircon minerals, which date back to the Archean era—an epoch spanning from 2.5 to 4 billion years ago, when scientists suspect the first continents began to coalesce.

A pivotal point raised by researchers from China and Australia last year posits that Archean zircons must have formed via subduction processes—where tectonic plates collide, pushing material towards the surface. This idea, however, strongly interlinks the concept of plate tectonics with the very genesis of continents.

Contrary to the subduction-centric theory, Hernández Uribe’s analysis reveals that such geological processes may not have been necessary for forming Archean zircons. Instead, his research suggests that these minerals could arise from conditions related to high pressure and elevated temperatures linked to the melting of the Earth’s primordial crust. Through simulations and calculations, he concluded that the same zircon signatures emanate from this alternative process, possibly offering a more compelling match to the historical mineral compositions.

This finding generates crucial implications, not just for the debate on when and how the first continents formed, but also raises questions about the timeline for the onset of plate tectonics on Earth itself. If the model supporting subduction is accurate, it would push the advent of continental movement back to a mere 500 million years after Earth’s formation—at an astonishing 3.6 to 4 billion years ago. Conversely, if early continents originated from melted crust, the commencement of tectonic activity could have occurred significantly later.

Hernández Uribe emphasizes the singularity of Earth within our solar system, as it is currently the only known planet exhibiting active plate tectonics similar to those we observe today. This uniqueness presents both intrigue and complexity within the field of geology, as scientists strive to understand not only Earth’s past but also the conditions that sustain such dynamic geological processes.

As the discourse surrounding the formation of continents continues to evolve, Hernández Uribe’s findings serve as a powerful reminder of the need for critical reevaluation of established scientific theories. An open-minded approach to new research may one day unlock answers to the mystery of our planet’s formative years and refine our understanding of geology as a whole.

Leave a Reply