In recent decades, California has experienced an unparalleled rise in Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) development. This phenomenon, characterized by residential areas encroaching upon natural landscapes, places a significant number of residents at heightened risk for a multitude of climate-related disasters, including wildfires, floods, and landslides. A new study spearheaded by researchers at UC Santa Cruz elaborates on this urgent issue, revealing how the state’s severe housing crisis may be exacerbating this trend. With more than a third of Californian households now situated at the very brink of wilderness, the implications for urban planning and sustainability are profound.

The implications of this trend go beyond immediate safety concerns. Extensive WUI development not only increases the likelihood of devastating wildfires, but it also adversely affects local wildlife habitats and raises greenhouse gas emissions due to lengthened commutes. The interplay between urbanization and environmental stability begs an exploration of the underlying factors driving this sort of residential growth.

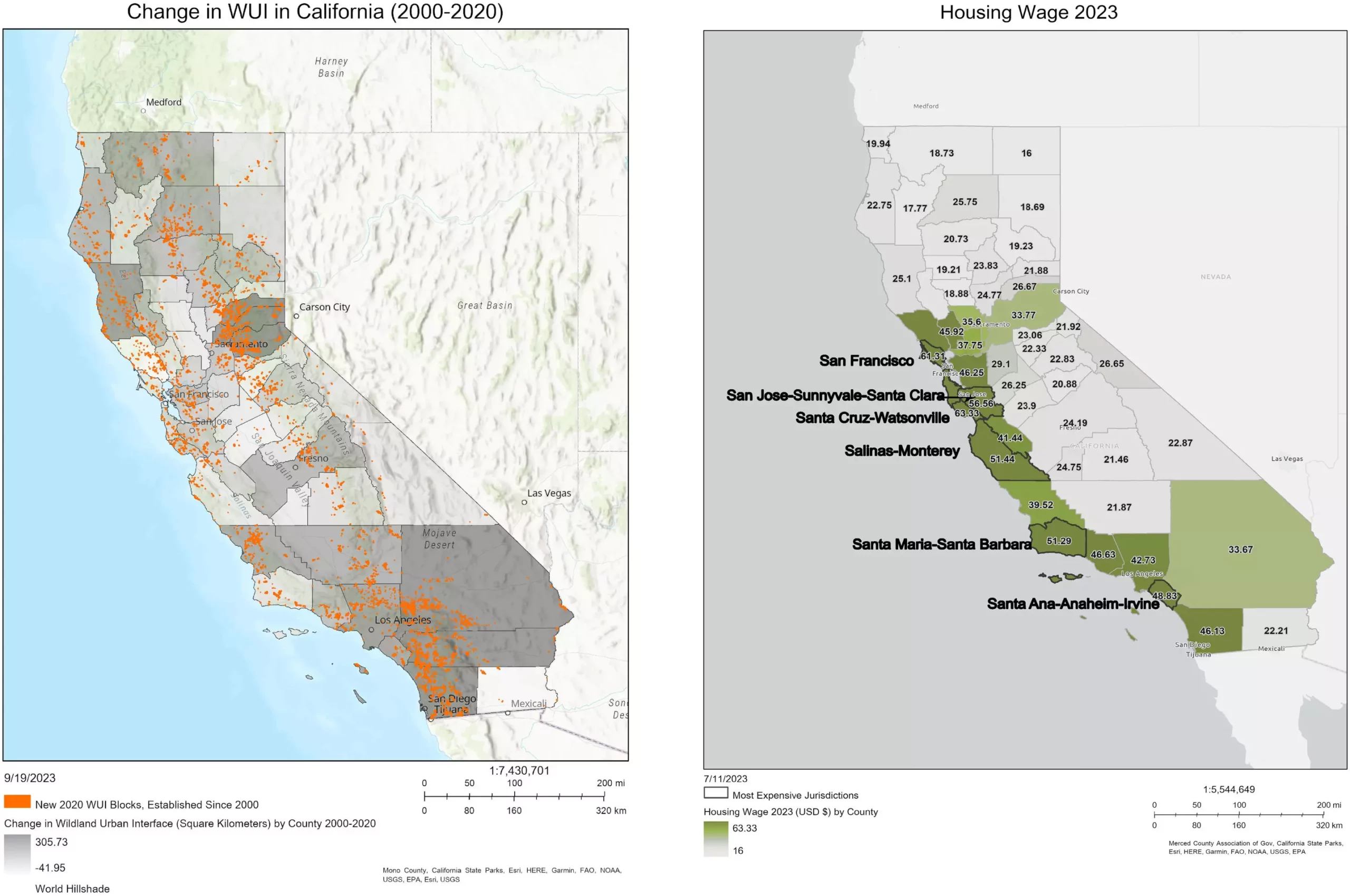

According to the research, historical motivations for moving into WUI areas often revolved around personal connections to the land, generational ties, or a deep yearning for closer communion with nature. However, the new findings suggest a dramatic shift; housing affordability has emerged as the primary driver of recent migration patterns toward these areas. As urban housing costs soar unpredictably, many Californians are being inexorably pushed into these risky zones.

Faculty members including Sociology Professor Miriam Greenberg, who leads this groundbreaking study, posit that understanding WUI growth necessitates a multidimensional approach that incorporates perspectives from both social sciences and environmental studies. This is a crucial paradigm shift as it emphasizes that ecological dynamics cannot exist in isolation from urban development trends. This recognition could offer invaluable insights into how socio-economic factors influence individuals’ choices regarding where to live amidst increasing environmental risks.

The characteristics of the WUI landscape reflect deepening socioeconomic divides. The study anticipates stark demographic differences within various types of WUI developments. On one hand, WUI “interface” zones that stretch from urban areas into wildland are predominantly populated by middle-income individuals, often employed in city jobs. On the other hand, the remote “intermix” developments promise a more complicated social fabric—housing offerings may range from high-priced estates for the wealthy to more pedestrian options, including modest older homes, trailers, and makeshift living spaces.

This uneven landscape points to a broader issue of inequality, revealing how affordability-driven migration not only exacerbates the socio-economic divide but also places marginalized communities in greater peril when climate-related disasters occur. The research highlights that while all residents face similar natural risks, disparities in wealth and resources create vastly different capacities for disaster preparedness and recovery. In this context, those drawn to the WUI for its affordability may find themselves disproportionately affected when calamity strikes.

The research argues for a reconsideration of how housing crises are framed within broader sustainability discussions. It emphasizes the intertwined nature of urban planning and climate resilience, suggesting that these subjects cannot remain siloed within policy frameworks. If policymakers truly aim to bolster communities against climate threats, they must acknowledge the social dimensions of housing affordability.

Co-authors, including Sociology Associate Professor Hillary Angelo and Environmental Studies Professor Chris Wilmers, advocate for an innovative fusion of housing stability and climate action. Solutions could range from improved affordable housing production and tenant protections in urban areas to the incorporation of sustainable practices like Indigenous land stewardship and habitat restoration. The collaboration between social scientists and environmental researchers could pave the way for more comprehensive, actionable strategies to address both the housing crisis and environmental degradation.

Ultimately, this new research emphasizes the necessity of expanding our understanding of urban sustainability. As cities grapple with the growing pressures of climate change, it is vital to recognize how deficiencies in affordable housing can compel residents toward increasingly precarious living situations in WUI environments. By integrating housing and climate strategies across various levels of governance, there exists a path toward creating safer, more equitable communities in California and beyond. The solution lies not just in confronting the pressing challenges of today, but in recognizing the systemic interconnections that shape our urban landscapes for generations to come.

Leave a Reply