In the ever-evolving landscape of biotechnology, the potential of bacteria as bio-manufacturers stands at the forefront of innovation. These single-celled organisms have the remarkable ability to produce a variety of materials that hold significant promise for human use, including cellulose, silk, and minerals. The sustainability aspect of bacterial production is undeniably appealing: it occurs at room temperature in aqueous environments, reducing the energy consumption associated with traditional manufacturing processes. However, harnessing these capabilities effectively presents its own set of challenges. The natural output of these bacteria is limited, both in quantity and speed, making industrial applications often unfeasible.

As scientists grapple with these limitations, a transformative approach is emerging—one that seeks to turn these microscopic entities into “living factories” capable of generating larger, more useful amounts of desired products in shorter periods. One particularly groundbreaking initiative is being led by Professor André Studart at ETH Zurich. His team has introduced a novel methodology that leverages the principles of evolutionary biology to enhance cellulose production in the bacterium Komagataeibacter sucrofermentans—a species already known for its natural high-purity cellulose output.

A Leap into Evolutionary Engineering

The core of Studart’s team’s strategy revolves around induced evolution, allowing them to generate a broad array of bacterial variants in a short time span. While K. sucrofermentans naturally produces cellulose beneficial for applications in biomedicine and sustainable packaging, its slow growth rate and limited cellulose yield have long been recognized as barriers. Julie Laurent, a doctoral student under Studart’s guidance, spearheaded an innovative research study published in the prestigious journal PNAS.

Laurent’s approach involved exposing the bacterial cells to UV-C light to induce random DNA damage, thereby fostering mutations. This step is crucial; without intentional impairment of the bacteria’s genetic material, there would be no chance for advantageous mutations to emerge. By placing these irradiated cells in the dark—thus preventing any inherent DNA repair mechanisms from kicking in—Laurent cultivated a population teeming with variations. Once the mutations were in place, these cells were encapsulated in miniature droplets of nutrient solution, allowing them to produce cellulose under specified conditions.

Innovation through Selection and Automation

Critical to the success of this research was the implementation of advanced sorting systems, crafted by chemist Andrew De Mello’s group, which enabled rigorous selection of the most successful cellulose-producing variants. With automation at the helm, the team could quickly screen hundreds of thousands of droplets, identifying those that yielded particularly high cellulose amounts. From this exhaustive sweep, four standout variants emerged—each capable of generating between 50% to 70% more cellulose than their wild-type counterparts.

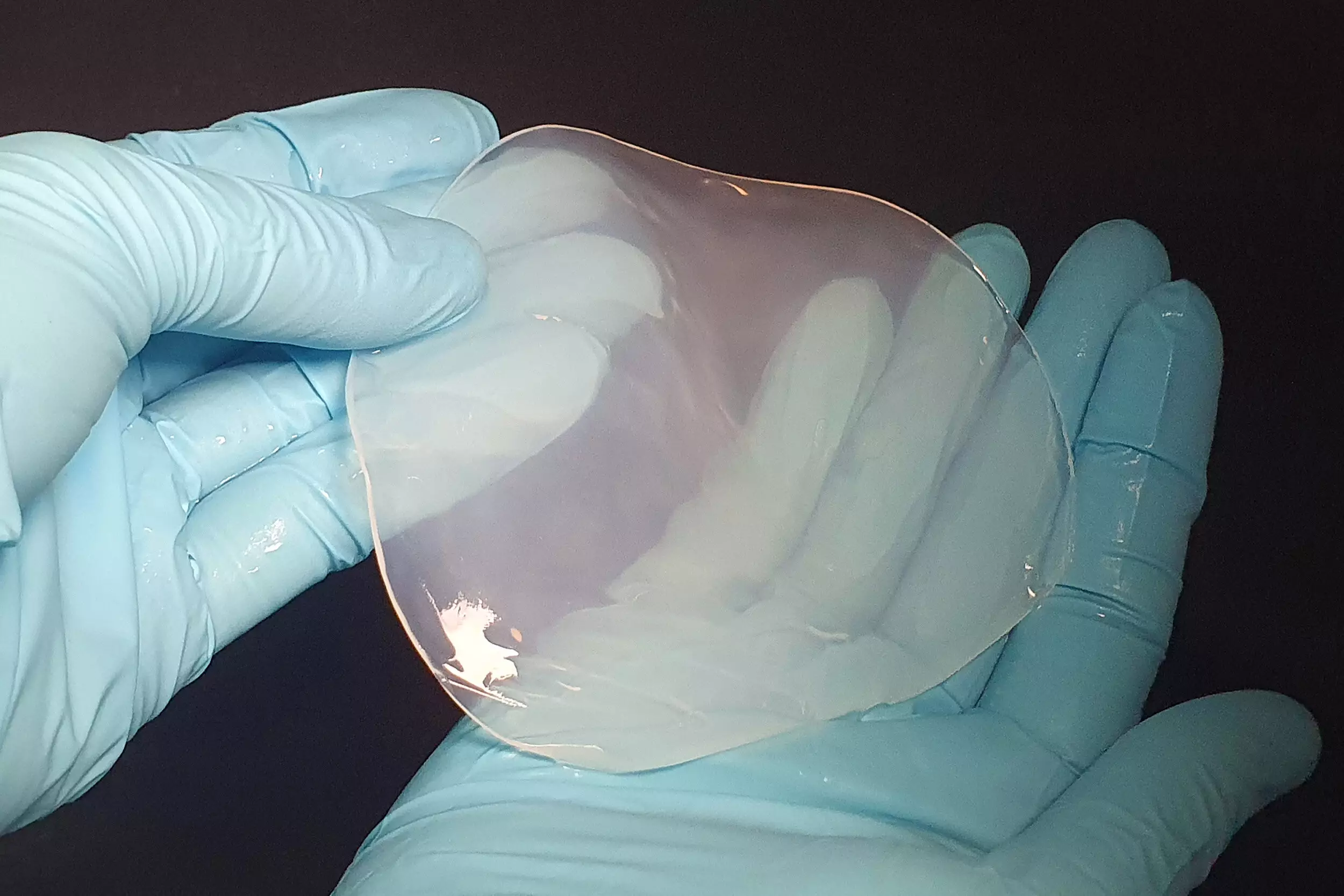

This acceleration—from basic biological properties to highly efficient production mechanisms—shows the potential for a paradigm shift in how we view bacterial applications. K. sucrofermentans variants can thrive and churn out cellulose not just at a greater rate, but also in larger physical formats, creating mats that are almost twice as heavy and thick compared to the non-mutated strains.

Deciphering the Genetic Mysteries

What makes this advancement particularly fascinating is the genetic analysis conducted on the successful variants. Interestingly, despite their remarkable cellulose production capabilities, it was discovered that the genes directly responsible for cellulose generation had remained unchanged. Instead, the mutations occurred in a gene responsible for encoding a protease—an enzyme that breaks down proteins. The implication here is alarming yet intriguing: with the regulatory mechanism that typically limits cellulose production disrupted, the cells are free to produce cellulose unopposed.

This line of inquiry opens doors to numerous possibilities. While the initial focus has been on cellulose production, the versatility of the chosen method hints at broader applications. The technique, which initially aimed at producing proteins and other enzymes, has now successfully ventured into the realm of non-protein materials. Professor Studart heralds this achievement as a significant milestone in materials research, marking a shift in how we might utilize microbial processes for industrial purposes.

Future Directions: Bridging Research with Industry

With a patent already filed for these unique bacterial variants and their production methods, the groundwork has been set for real-world application. Collaborative efforts between academic research and industrial partners loom on the horizon, promising to translate these laboratory findings into commercially viable solutions. The evolution of K. sucrofermentans could very well signify a new era where biology seamlessly integrates with industry, positioning these microorganisms as essential players in the sustainable production of materials that align with global environmental goals.

This breakthrough not only showcases the ingenuity of bioengineering but also emphasizes the importance of revisiting foundational biological principles—nature’s own strategies can guide us toward unprecedented advancements in materials science.

Leave a Reply