The history of the plague is one that has haunted humanity, with its presence felt significantly in the fabric of societal development across centuries. The newly research unveiled sheds light on something profoundly fascinating: the bacteria that cause the plague, Yersinia pestis, have been evolving in a way that decreases their virulence over time. This evolution has allowed them to persist through three major pandemics, each profoundly impacting populations and cultures, and raising questions around human resilience and pathogen adaptability.

The Pandemics and Their Legacy

The initial wave of plague, known as the Plague of Justinian, swept across the Byzantine Empire in the 6th century and inflicted devastation for approximately 200 years. This was followed by the infamous Black Death in the 14th century, which indiscriminately took the lives of an alarming 25 to 50 million people in Europe, constituting nearly half of continental Europe’s population at the time. Last but not least, the third major outbreak began in the 1850s in China and continues to linger, reminding us of both the historical impact and the ongoing relevance of this pathogen in our contemporary landscape.

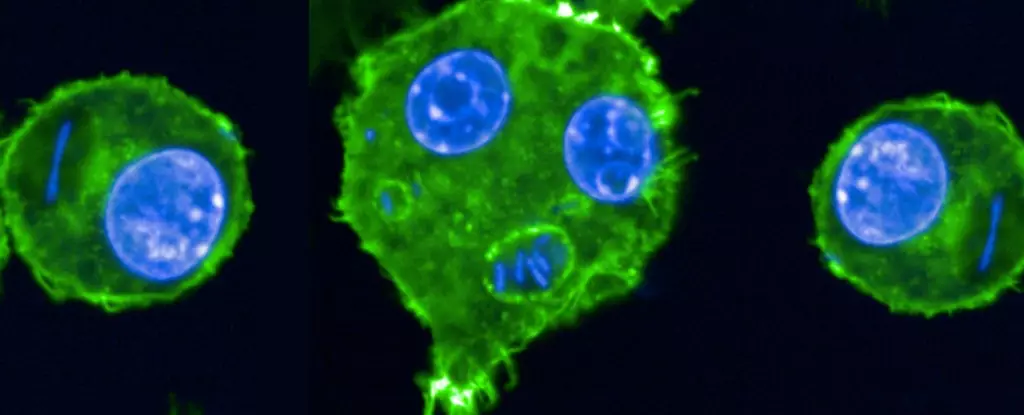

What is particularly compelling about this research is not merely its focus on the scale of human loss but the underlying mechanics of the disease itself. The finding that Yersinia pestis has evolved to become less deadly is a testament to the delicate balance that pathogens strike in a host-dependent relationship. By becoming less virulent, the bacteria enhance their chances of survival, spreading more effectively among individuals and prolonging their presence within human populations.

The Role of Adaptation

The implications of this evolution are significant. The ability of pathogens to adapt is not unique to the plague; however, the historical context in which this occurs offers a stark reminder of lessons learned and potential strategies for future pandemic management. As highlighted by microbiologist Javier Pizarro-Cerda of the Pasteur Institute, a comprehensive understanding of how such pathogens function can help anticipate outbreaks and develop strategies to counteract them.

In addressing the mechanisms behind decreased virulence, recent experimental evidence illustrates that lower pathogenicity allowed the plague to persist by ensuring that hosts lived long enough to spread the bacteria to others. This adaptation contradicts the traditional view that increases in pathogenicity are the ultimate goal for organisms, instead highlighting a fascinating evolutionary strategy that favors symbiosis over destruction.

The Modern Implications

While modern medicine has equipped us with antibiotics capable of treating the plague effectively, this research opens doors to understanding other infectious diseases and how they might evolve under similar circumstances. It challenges our perception of pathogenic threat, suggesting that the narrative should be less about outright eradication and more about coexistence and management.

This newfound insight serves not only to enrich historical knowledge but urges us to reconsider our strategies in combating infectious diseases. The phrase “knowledge is power” rings especially true in this context; understanding the evolutionary trajectories of pathogens can inform public health policies, potentially steering us away from panic and towards preparedness. The study acts as both a historical reflection and a contemporary guide, highlighting the timeless dance between humanity and the pathogens that have shaped our destiny.

Leave a Reply